Of course I got comments on my post about orchestras playing and playing the standard masterworks. I said this hobbled them as artistic institutions, and paralyzed them in other ways, restricting their imagination even in things as mundane as press releases. If you limit your thinking in the central thing you do, the work that takes up most of your time and energy, of course that has consequences.

But of course not everyone agreed. Which isn’t a surprise. My thought isn’t exactly orthodox, and of course many people love hearing the standard works over and over. That’s what the orchestral enterprise has been about, and it couldn’t have survived if people didn’t get something from it. But the big question is whether this focus on the same old pieces — great as they are — is sustainable.

I think not, for reasons I’ll shortly say more about. But right now I want to think about an objection made in a Facebook comment. This is a very good person, someone who does good work with a very good orchestra. She said — and certainly others think this — that there’ soothing wrong with playing Beethoven’s Fifth, because there’s always someone who hasn’t heard it.

But they also haven’t heard Ligeti!

Part of my Facebook response was something Sir Nicholas Kenyon wrote some years ago, he being a British critic — at one time classical music critic for the New Yorker in the U.S. — who went on to become director of the BBC Proms concerts and then Managing Director of the Barbican Centre in London. He wrote that, for people first coming to classical music, everything was new, new pieces as well as old.

But I’d go further than that. When we say that there’s always someone who hasn’t heard Beethoven — and when we use that as a defense of standard classical programming — we make an implicit assumption. Which is that hearing Beethoven is at the core of what classical music is about, and that in fact hearing the entire old canon is central. And that people will be nourished by hearing it. And (if we,re defending standard classical music practice) that they’ll be nourished by not hearing terribly much of anything else.

Miseducation

I can’t agree. The standard canon is only a selection of what classical music offers. It leaves out most everything before the Baroque era, much of the 20th century, and everything from our time. I was listening lately to one of Stravinsky’s marvelous late pieces, Canticum Sacrum (which is partly 12-tone), and grieving that you could spend a lifetime in classical music and never hear it live. And that you’ll only rarely hear even his most wonderful neoclassical works — the Violin Concerto, Apollo, the Cantata, Symphony of Psalms — to name just four.

And that’s just Stravinsky. (Who’s worth citing, since we revere him as one of the greats while ignoring nearly everything he wrote.) If we think that exposure to our standard programming gives new people an education in classical music, then we’re miseducating them, as we’ve miseducated ourselves.

Too mellifluous

And we’re also keeping classical music far from current culture, preserving it (again, even though the masterworks are important and powerful music) as a nostalgia trip. This won’t sit well with many of the new people we want to attract, because we’re asking them to accept a hidden assumption — that great art music is by nature largely mellifluous. Because, after all, that’s how the standard classical masterworks sound: rich with soft or grand chords and melodies.

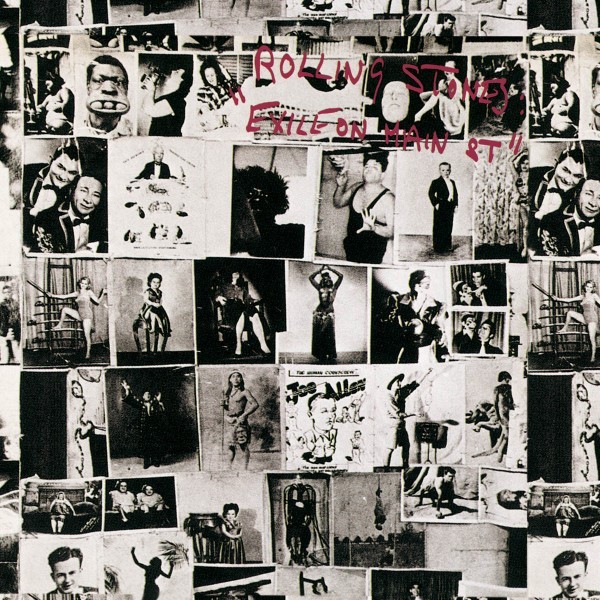

Which, by itself, is fine. I’m not saying classical music music from the past is bad. But, taken as a whole (and heard day after day, week after week) it doesn’t sound like our contemporary musical culture. We have mellifluous music today, but much of what we hear — especially in the smarter precincts of nonclassical music — isn’t mellifluous. Electronic dance music has a harder edge. Indie rock can be full of noise. Even in classic rock (as I wrote not long ago in a post in which I talked about a track from the Stones’ Exile on Main Street), the electric guitars generate such a swarm of clashing overtones that even a simple E major chord sounds fierce.

Which, by itself, is fine. I’m not saying classical music music from the past is bad. But, taken as a whole (and heard day after day, week after week) it doesn’t sound like our contemporary musical culture. We have mellifluous music today, but much of what we hear — especially in the smarter precincts of nonclassical music — isn’t mellifluous. Electronic dance music has a harder edge. Indie rock can be full of noise. Even in classic rock (as I wrote not long ago in a post in which I talked about a track from the Stones’ Exile on Main Street), the electric guitars generate such a swarm of clashing overtones that even a simple E major chord sounds fierce.

Bob Dylan, on his earliest albums, will do things on his harmonica that clash with the chords he’s playing on his guitar. Nor is his voice exactly mellifluous. And he’s central to our current musical culture.

So if we insist on playing mostly mellifluous old music, we’ve stepped away from modern life. We in classical music may think of nonmellifluous music (music, let’s say, with a lob of dissonance) as the advanced course, but for most people today, that’s not true. Nonmellifluous music is mother’s milk to them.

So when they hear what we offer, many of them — whether they formulate this thought or not — will think that something’s missing. And the more we insist that we’re giving them the greatest musical art, the more they’ll think that something’s wrong.

A story, which I know I’ve told here before. Years ago, in my pop music days, I had a girlfriend who thought she might like to hear classical music, though most of her musical culture was pop. So one Sunday morning, as we had breakfast in my apartment, she asked me to play something classical.

I put on Handel’s Water Music. Or anyway something like that, something Baroque. After a little while, my girlfriend asked:

“Why isn’t classical music more noir?”

I took off the Baroque music, and put on Berg’s Lulu Suite.

“That’s what I mean,” she said. “Why doesn’t more classical music sound like that?”

Original Content: Too Mellifluous

No comments:

Post a Comment